The term “muscle pliability” has been in the news around the NFL quite a bit. Tom Brady and his trainer, Alex Guerrero, claim that making muscles pliable is the best way to sustain health and performance. How true is that claim? While it’s a great descriptive term, we are going to shed some light on what it really means and how to create muscle pliability.

Defining Words

Our performance coaches, sports medicine specialists, and tissue therapists all find it to be a useful term. Pliable expresses some of the important qualities of muscle. According to Miriam-Webster Dictionary here’s what pliable means:

Pliable

a: supple enough to bend freely or repeatedly without breaking

b: yielding readily to others

c: adjustable to varying conditions

That’s a pretty good description for many of the qualities we want in the tissue of an athlete (or any human for that matter). The problem is that it’s being mixed up with a lot of inaccurate and confusing statements.

Our Sports Medicine Specialist, Misao Tanioka, says that “the word pliability, in my opinion, depicts the ideal muscle tissue quality. It is similar to suppleness, elasticity, or resilience. Unfortunately, I believe some of the explanations offered by Mr. Brady and Mr. Guerrero have created some misunderstanding of what ‘muscle pliability’ really is.”

Let’s try and separate some of the myths from what is true.

Myth 1: Muscles that are “soft” are better than dense

That depends on what qualifies as “soft” muscle. Tissue Specialist Cindy Vick has worked on hundreds of elite athletes, including NFL players and Olympians across many sports. “Soft isn’t a word I would use for an athlete. When I’m working on an elderly client, I often feel muscles that could be called soft; they’re not dense. That’s not what I feel when working on elite athletes. Athletes who are healthy and performing well have muscles that have density without being overly tense and move freely. The tissue is still smooth and supple.”

This muscle quality is affected by many factors, ranging from stress, competition, nutrition, training, and recovery. At Velocity, maintaining optimal tissue quality is a constant endeavor. Proper self-myofascial release, various stretching techniques, and manual therapy are all part of the equation.

MORE INFO: Mobility vs Flexibility: They are different and it matters for athletes

Myth 2: Dense muscles = stiff muscles = easily injured athletes

Relating these terms in this way grossly over-simplifies reality and is in some ways completely wrong.

You have to start with the operative word: “dense.” Tanioka says, “Dense tissue can be elastic; elastic tissue is resilient to injury. What we have to look for is inelastic tissue.” Cindy Vick adds that “if you mean ‘dense’ to refer to a muscle with adhesions, or that doesn’t move evenly and smoothly, then yes, that’s a problem.”

Scientifically, stiffness refers to how much a muscle resists stretch under tension. It’s like thinking about the elastic qualities of a rubber band. The harder it is to pull, the stiffer it is. If a muscle can’t give and stretch when it needs to, that’s bad.

Imagine a rubber band that protects your joint. When a muscle exerts a force against the impact of an opponent or gravity, stiffness can help resist the joint and ligaments from being overloaded and consequently injured.

“I agree with Mr. Brady’s statement about the importance of a muscle’s ability to lengthen, relax and disperse high-velocity, heavy incoming force to avoid injury,” says Tanioka. “However, I think that athletes also must be able to exert maximum power whether actively generating force or passively resisting incoming stress, which requires the ability to shorten and be taut and firm as well as lengthen. The ability of the tissue to be durable and contractile is just as important as to elongate and soften when it comes to performance and injury prevention.”

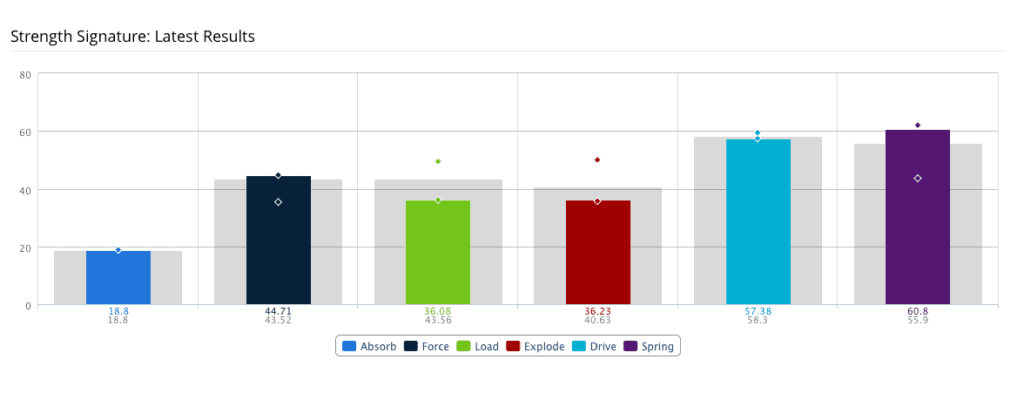

In the view of our experts, it’s not about dense, soft, stiff, or other qualitative words. Instead, they emphasize developing function through different types of strength qualities athletes need. Athletes must prepare for the intense stress and strain their muscles will face in their sport. They need to blend the right strength training with mobility and flexibility.

Myth 3: Strength training makes muscles short

“It’s an old wives’ tale that took hold when bodybuilding techniques had a big influence on strength and conditioning. A muscle can be incredibly strong without sacrificing any range of motion” according to international expert and President of Velocity Sports Performance, Ken Vick, who has worked with athletes in 10 Olympic Games and helped lead the Chinese Olympic Committee’s preparation efforts for 2016 Rio Olympic Games.

“I’ll give you two great examples: Gymnasts are, pound-for-pound, very strong and incredibly explosive, yet they are known to be some of the most flexible athletes. Olympic weightlifters are clearly some of the strongest athletes in the world and are also generally very flexible. They spend practically every day doing strength training and their muscles aren’t ‘short’.”

RELATED: Why Athletic Strength Is More Than Just How Much Weight Is on The Barbell.

In fact, proper lifting technique demands excellent flexibility and mobility. For example, poor hip flexor flexibility or limited ankle mobility results in an athlete who probably cannot reach the lowest point of a back squat. Our proven methods combine strength training with dynamic mobility, movement training, and state of the art recovery technology to help our athletes gain and maintain the flexibility and mobility required for strength training and optimal performance on the field of competition.

Myth 4: Plyometrics and band training are better for pliability

We hear these types of claims time and again from coaches, trainers, and others who are quoting something they’ve read without much knowledge of the actual training science. Our muscles and brain don’t care if the resistance is provided by bodyweight, bands, weights, cables, or medicine balls. They can all be effective or detrimental, depending on how they are used.

Sports science has shown that manipulating different variables influences both the physiological and neurological effects of strength training. Rate of motion, movement patterns, environment, and type of resistance all influence the results.

Truth: Muscle Pliability is a good thing

Like so many ideas, muscle pliability is a very good concept. The challenge lies in discerning and then conveying what is true and what is not. An experienced therapist can, within just a few moments of touching a person, tell whether that tissue is healthy. A good coach can tell whether an athlete has flexibility or mobility problems, or both, simply by watching them move.

In either case, it takes years of experience and understanding of the human body and training science, like that which is possessed by the performance and sports medicine staff at Velocity, to correctly apply a concept like muscle pliability to an athlete’s training program.