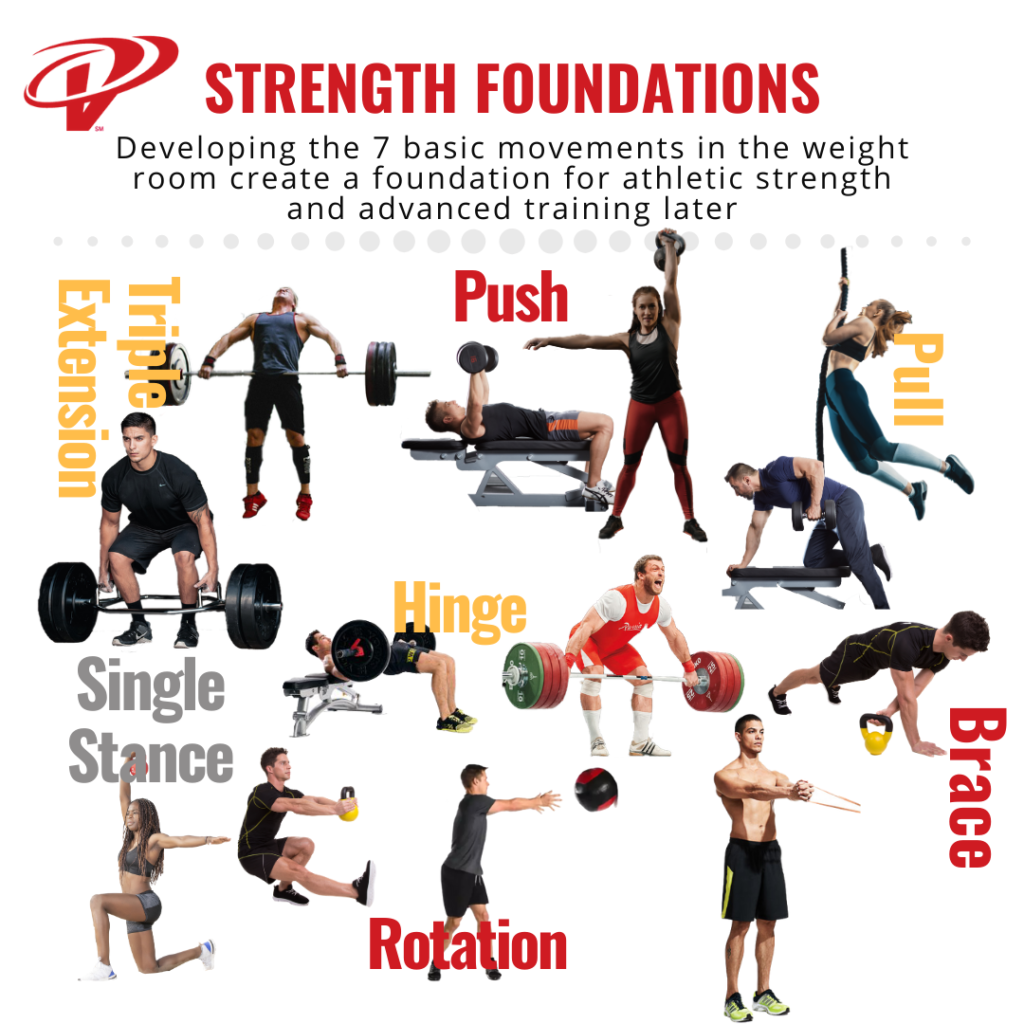

There are seven strength training movement patterns all athletes need to master. To understand why you have to understand why athletes strength train in the first place.

Building a base of general strength is useful for almost every athlete. While many people pursue sport-specific training right away, a base of strength developed with General Physical Preparation lays a foundation to build on.

It’s even more helpful if all 7 of the fundamental movement patterns are being strengthened. Athletes don’t want gaps when building a strong foundation. These movement patterns reflect the big categories of athletic movement.

Want to learn more?

Movements Over Muscles

Strengthening movement patterns means you are not only hitting the right muscles but working on the correct movements. After all, that’s how the brain works; in movements, not muscles. You are training the right patterns for

This wasn’t always the case in strength training. For many years (and still today), bodybuilding influenced athletic strength training. One of its basic approaches is a focus on isolating individual muscles to add maximum stress and growth. That’s great if we are only trying to build muscle. But if we want to improve movement, we need to train the muscles and the brain.

It’s easy to forget, but strength training is just movement training with added resistance. We need to strengthen movement patterns in all three planes of motion to build a complete athlete. Working on these seven strength training

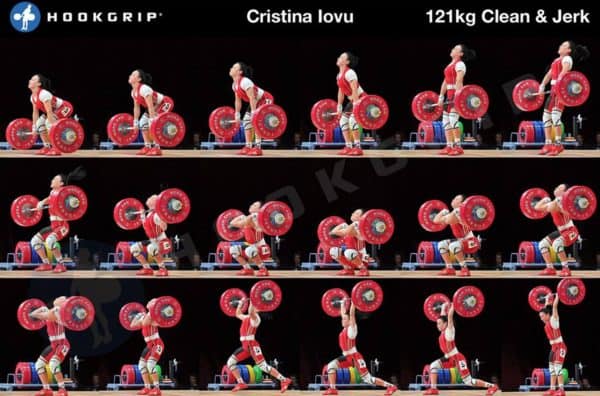

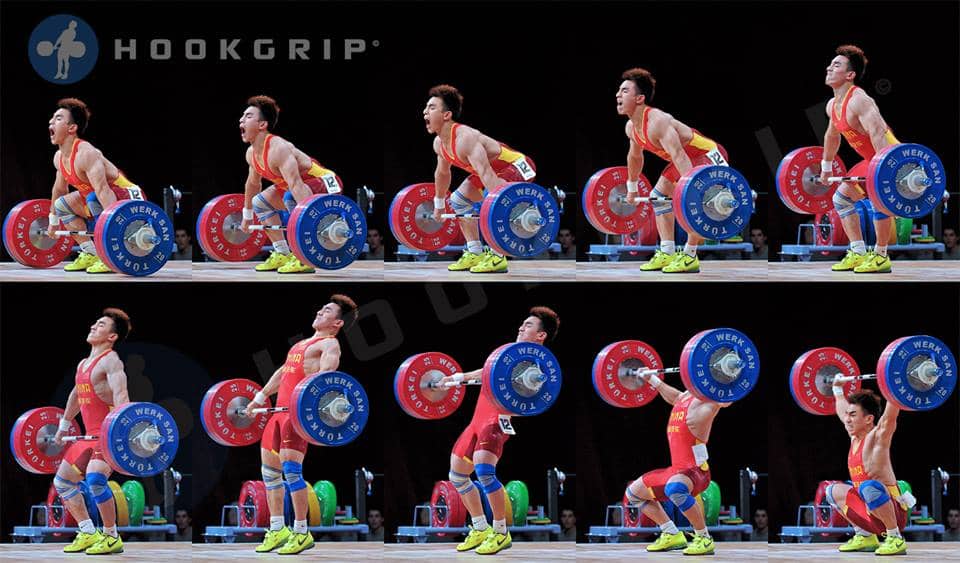

Multi-Segmental Extension.

Or the similar action of the lower body in a volleyball player going up for a block. How about the extension of the lower body and trunk on a football tackle.

The basis of most sporting movements is the coordinated extension of multiple joints and muscles of the lower body. Just picture a sprinter simultaneously extending their hip, knee, and ankle joints as they propel their body forward out of the starting blocks.

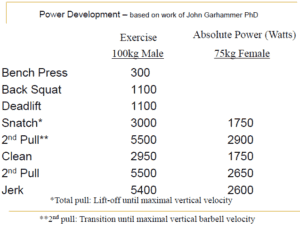

Coordinated extension can be seen all over in sports and in the weight room. Squats, deadlifts, jumps, and Olympic lifts all fall into this category.

Single-Leg Stance

Another fundamental human movement pattern is single-leg stance. Because human gait involves single-leg support variations, we find this everywhere in sports where athletes are moving over the ground.

A vital element of this pattern is that the left and right sides of the lower body have different things happening between them. This unilateral focus changes both the application of force and the requirements for added stabilization in the core, pelvis, and leg.

In the weight room, we have true single-leg stances or split stances that create unequal loads between two legs. While doing a step-up or a lunge, we have moments of single-leg stance. IN split squats, lateral squats, and Bulgarian split squats, we might have both feet in contact, but the emphasis of force is on one more than the other.

Hip Hinge

Another lower body action we see is hinging at the hip. This might also combine with some extension at the torso. These types of movements are coordination of force and stability through the posterior chain muscles.

In sports, we might see examples in a wrestler bridging, trying to get their shoulders off the mat, or while standing and trying to throw an opponent backward. Or if we observe a track athlete sprinting at full speed and focus on how their leg moves backward to hit the track by extending at the hip.

In strength training for sports exercises like the Romanian Deadlift, Kettlebell Swing, and Hip Bridges are all used for this movement pattern.

Upper Body Push

When we have a coordinated extension of joints in the shoulder, arm, and wrist, we consider this a push. We can classify these as vertical or horizontal push motions based on the plane of movement.

In many sports, we have motion where an athlete is pushing against an object or another player. You can picture the football lineman pushing an opponent.

It’s also a component in many throwing and swinging motions. During the second half of these and the follow-through, there is a multi-joint pushing motion.

The bench press is probably the most common Upper Body Push exercise known. Because of the plane of motion, we’d consider this a horizontal push. An overhead press, on the other hand, would be a vertical push.

Upper Body Pull

This is the inverse of the push and is the coordination of flexion in those upper body joints. While it’s slightly less common than pushing, it’s critical in many sports. The “pull” in swimming strokes is what we would consider a vertical pull. It could also be a rock climber or gymnastic pulling their body upward.

Horizontal pulling occurs in wrestling and grappling sports as opponents battle for position. The same can be true of a defensive lineman trying to get past a blocker. Another common horizontal pull would occur in rowing, kayaking, or canoe.

Chin-ups and pull-ups are the quintessential vertical pulls. However, pulldowns and other cable exercises can fit here. For horizontal pulling, we have lots of rows with dumbbells, barbells, and cables.

Bracing

This isn’t a movement pattern at all. In fact, bracing is actually an anti-movement pattern. In their core, athletes need to control and transfer force from the upper to lower body.

The efficient transfer of force often means limiting motion so that force isn’t lost. Resisting flexion, extension, and rotation in the pelvis and the spine is critical for efficient and explosive movement.

For instance, let’s consider a wide receiver sprinting at full speed down the field. As their foot strikes the ground, they want to transfer force into the turf to propel them forward. If their pelvis drops and their core collapsed when they hit the ground, they would lose some of that force. Instead, they want their core to be solid as a pillar and transfer all that force into the ground.

We strengthen this pattern through exercises such as planks and stability chops or lifts with cables. Any exercise that focuses on the stability of the core while under load helps with bracing.

Multi-Segment Rotation

Finally, we have the coordinated rotational action that builds up from the lower body, through a stable core and transfer into the upper body. It is easy to picture this in sports from a batter swinging to a quarterback throwing. Sports such as golf, tennis, and hockey all involve rotation to swing an implement.

There are elements of other patterns here; multi-segment extension, bracing and upper body pull/push. The reason this is a fundamental pattern in itself is the coordination of the these in the transverse plane of motion.

In the weight room, we may use various cable exercises or medicine balls to strengthen rotation. We can also use barbell landmine or other kettlebell exercises with rotational patterns to achieve this goal.

Train Movement Patterns Not Muscle Groups

Movement patterns, not muscles, is how the human brain controls movement. Motor control is organized in coordinated patterns, not individual muscles. The seven fundamental strength training movement patterns are;

- Multi-Segmental Extension

- Single-Leg Stance

- Hip Hinge

- Upper Push

- Upper Pull

- Bracing

- Multi-Segmental Extension

By building our training approach from these seven strength movement patterns, we serve athletes better. Better transfer from the weight room to sports. Building movement proficiency in the weight room in all seven movement patterns is a building block for every athlete.